At Arundells, we practise Preventive Conservation. This is a holistic approach to preservation which works on the principle that prevention is better than cure. Deterioration due to natural aging is inevitable; instead, we aim for “careful management of change.”

Arundells is a historic house presented as a home, which adds an extra conservation challenge because locking objects away in carefully controlled cases would detract from the “spirit of the place.”

Read on to find out more about the threats to the collection at work on a day-to-day basis and what we do to keep the stuff at Arundells safe.

Physical forces

Ceramics are created by firing at high temperatures and, therefore, can tolerate light and extreme environmental conditions. Their Achilles Heel is fragility. This Ming bowl was famously dropped by the removal team when Sir Edward was moving out of Downing Street in 1974 and subsequently repaired. Old damage and repairs are not necessarily undesirable in a museum context – they can contribute to our understanding of the history of the object and its ability to “tell a story.” However, in this case, the repairs are deteriorating and damp is entering along the old cracks, staining the porcelain body. This is making the bowl unstable and it needs remedial conservation before more damage occurs.

Mechanical damage, or wear-and-tear, can also develop over time. “Patina” is not necessarily a bad thing, as long as the object is stable and useful and its original appearance hasn’t been significantly compromised.

Dust and dirt are generated by humans shedding skin, hair and clothing fibres, the house generating particles of plaster, stone and paint as it shifts, and is blown in from outdoors. As well as being unattractive, it can “cement” onto objects in high humidity. It is a food source for insect pests and, when the dirt contains pollutants, can corrode surfaces. Removing dust and dirt increases the risk of accidental damage – cleaning the decks of this model of Morning Cloud is going to require a curator armed with cotton wool swabs and nerves of steel to work around the fragile rigging!

Some physical damage is unavoidable; the rest can be mitigated using common sense. Correct handling and cleaning techniques, reducing object movement, and sensible presentation is key.

This is why we ask everyone not to touch the collection. This Tang dynasty pottery ox is cute, but his nose shows a loss of the remaining slip decoration and greasy deposits from repeated touching with bare hands. Earthenware is porous so this dirt will be difficult to remove.

Regular housekeeping prevents dust and dirt building up. At Arundells we have a closed season, during which we “put the house to bed” and carry out a traditional winter clean from cornices to carpets.

Light

Light is essential for viewing collections, and the effect of evening sun filtering down the stairs at Arundells is spectacular.

However, light causes cumulative and irreversible damage to collections. Sources can be natural or artificial. All wavelengths are damaging: the visible spectrum, infrared radiation and ultraviolet light (UV).

Light is electromagnetic radiation – a form of energy. When it falls on a surface it induces photochemical changes in the molecules of materials. Cumulative exposure, wavelength and the sensitivity of materials affect the extent and nature of light damage to objects.

Light damage can be seen on the George III desk in the Study by comparing the colour of the wood that has been protected inside the cupboards with the surfaces that face the window. This has weakened the structure of the wood – you can see a joint beginning to come apart at the top of the left-hand cupboard.

Watercolours are very vulnerable to light damage. This is a detail of ‘Summer amusements at Margate’ by Thomas Rowlandson showing how the vibrant pigments have faded, losing information about original appearance of the artwork in the process.

For conservation purposes, the amount of light falling on a surface is measured in lux (lumens per square metre). UV radiation is measured as a proportion of UV to visible light for a particular source in microwatts per lumen.

The visible spectrum is useful for being able to see (!) but we try to keep levels to 50-100 lux, because all rooms at Arundells contain materials that are photosensitive: works on paper, textiles, and photographs. We monitor light levels with spot checks using a handheld light meter. Cumulative exposure to the hand-painted Chinese wallpaper on the stairs is monitored using a blue wool dosimeter. The area to the right of the wool which has not been protected by the strip of card shows that an amount of light damaging to the most vulnerable materials has been falling, but is under control.

We control light levels using sun blinds in combination with existing curtains, blinds and shutters and reduce the time they are open as much as possible.

Incorrect temperature and relative humidity

Relative humidity (RH) is a ratio, expressed as a percentage, of the amount of water vapour held in a specific amount of air compared to the maximum amount of water vapour that the same amount of air could hold at the same temperature and pressure. The higher the temperature, the more water vapour the air can hold. RH is more directly damaging to objects than temperature but the two are interrelated, so we consider them together.

High RH increases the risk of mould and rusting and creates favourable conditions for insect pests. Low RH causes dessication, shrinking and cracking of materials.

Most damaging, though, is constantly fluctuating levels. Objects expand and contract as they adsorb and desorb moisture, which breaks down their physical structure.

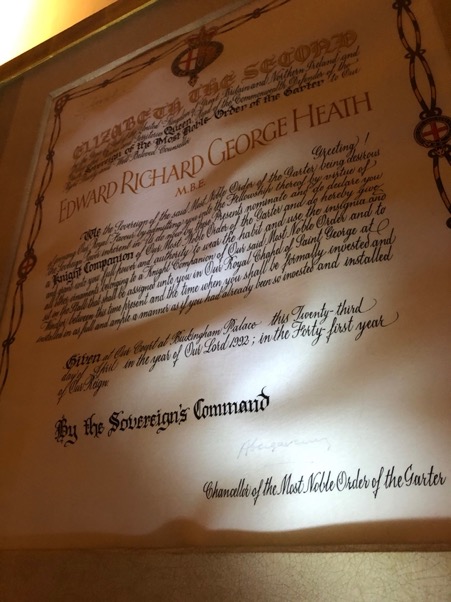

Parchment is hygroscopic – it absorbs moisture readily. Sir Edward was created Knight of the Garter on 23 April 1992. When viewed in raking light, his parchment warrant shows some significant cockling caused by humidity.

Controlling environmental conditions is essential but difficult in a historic house. We do our best with the central heating system and are happy to have a new boiler! We store materials that are more sensitive to damp, such as metals, in the drier central part of the building and use a dehumidifier in the Cartoon Corridor where there are a lot of works on paper and a tendency to mould.

The recommended parameters are a temperature of 16°C to 20°C and RH between 45% and 65%. The eagle-eyed among you will have spotted our data loggers, which continuously monitor temperature and RH. Arundells suffers from damp – not surprising for an old house by a river – but you can see from the screenshot of our Library data below that we keep the RH (blue) just about within the required levels although the temperature (red) has been low, especially during the February cold snap.

Insect pests

Insect pests are a common cause of damage to collections. They are categorized by the type of material they eat and therefore damage.

These adaptations to the tartan curtains in the Library are the work of clothes moth larvae. Adult moths lay their eggs on the textile and the larvae feed on it once they have hatched – keratin, the structural protein of wool, is a valuable foodstuff for them.

Woodworm, or the common furniture beetle, lay their eggs in crevices in wood like our attic beams. They are not fussy about whether it is hardwood or softwood. Once hatched, the beetle larvae tunnel through the wood for three or more years, feeding on the cellulose in the timber, before pupating and emerging through small circular exit holes as adults during spring and summer. There’s nothing boring about woodboring beetles…

It is impossible to prevent adult insects with the intent of laying their eggs on the collection entering the house.

Therefore, we monitor pest activity using sticky traps which are checked quarterly, more often in the active spring and summer months, to identify infestations as early as possible.

We create an inhospitable environment for pests by controlling the temperature and RH in the house as much as we can. Maintaining regular housekeeping routines and only allowing food in the kitchen reduces the number of food sources for adult insects.

Hopefully, you have found this brief introduction to the behind-the-scenes work at Arundells interesting and are reassured that we have not been spending the whole of lockdown eating biscuits (we have eaten somebiscuits). We are looking forward to opening up the unbroken, unfaded, uneaten collection to you as soon as we safely can this summer.