Written by Annie Boag

Leonard Bilson was the last canon to live in the house, until the 20th century, an educated man of previous high standing, who ended up in indelible infamy and in prison for 23 years, for the sake of unrequited love.

Leonard Bilson was born in about 1527. He was the younger son of Arnold and Clemence Bilson, the former, a brewer in Winchester. Arnold’s father, also an Arnold, had been born in Germany and his wife was allegedly the daughter of a Bavarian duke. Leonard’s brother Harman had six children, the eldest of which, Thomas, became Lord Bishop of Winchester, who was heavily involved in the translation of the King James Bible and is buried in Westminster Abbey between the tombs of Richard II and Edward III.

Leonard attended Merton College (St. Peter in the East) Oxford. From 1546, until 1554, he was “The Learned Master”(head master) of the Free School, Reading, Berks, and succeeded Leonard Cox. He became Prebendary of Winchester Cathedral in 1551 and a Canon of Sarum in 1552. He also acquired several other ecclesiastical appointments.

He became a residentiary canon in the year Catholicism returned to the cathedral. The moral strength of the chapter had been eroded by the rapid and brutal changes that they had endured. John Jewel,then a commissary, visited the cathedral in 1559 and 1560 when Bilson lived in this house. He wrote, “ The cathedral churches have become dens of robbers or more wicked” and found “very many things amiss, which we took grievously to heart.” In 1559 the spire had been struck by lightening and a fissure extended 60 feet downwards from the top. Some of the cathedral windows were broken and letting rain in and the canonical houses and the close wall were near to ruin. “ The spiritual decline and lack of discipline among all ranks of the cathedral clergy seems to have been almost as marked as the material destruction.”[i] Leonard obviously wasn’t the only bad apple in the barrel!

Elizabeth I disapproved of wives of the clergy living in the cathedral close but they were increasing in number and bringing about great social change. Leonard’s nephew Thomas was the first married Warden of Winchester College. In this atmosphere of moral decline and the increase in married clergy amongst his neighbours, Bilson became enamoured with Sir Richard Coton’s widow. He asked a friend, John Coxe, a former monk, to help him with some “love magic”. This severe error in judgement is still reported upon today. In the Sunday Times dated 30 August 2020;

“…It (Arundells) was also the home of a randy priest called Leonard Bilson, a 16th century canon who was jailed for sorcery. He had invited a young monk to the house to conduct a ceremony asking Satan whether the canon might “have his will” with a wealthy widow called Lady Cotton. All things considered, wouldn’t it have been easier to ask Lady Cotton. “

Perhaps he had asked and had been rebuffed. He obviously felt the need for help. Little was he to know that his spell was to cause him to become embroiled in the machinations of power at the highest levels.

On 14 April 1561 the aforementioned John Coxe was arrested at Gravesend, by customs officials, whilst attempting to secure passage to the Spanish Netherlands. He was found to be carrying a rosary, a breviary, money and letters to catholic exiles and also conveniently confessed to saying mass as part of “love magic”. On the 17th of April he was sent for clerical interrogation to Bishop Edmund Grindal, the new protestant Bishop of London. He admitted to saying masses for people and admitted that he did not believe that the new faith was the true faith. Whilst Grindal continued his interrogations the Privy Council sent men to round up those named in Coxe’s confession.

Under examination in the Star Chamber John Coxe admitted to saying mass in Leonard Bilson’s house (Arundells) to help Bilson obtain the love of Lady Cotton. Or as another source put it “Bilson…to have his will of the Lady Cotton caused young Coxe, a priest, to say a mass to call on the devil to make her his lady.”[ii]

On 23 June 1561 nine people appeared before the Court of Queen’s Bench and admitted their involvement in magic and were obliged to swear that they would have nothing more to do with evil spirits. In addition to John Coxe and Leonard Bilson, the “magicians” included an innkeeper, Hugh Draper, an ironmonger, Robert Man, a cleric, John Cockoyter, a salter, Fabian Withers, Rudolf Poyntell, a miller and a goldsmith, John Wright and Francis Coxe. They were all pilloried on the same day at Westminster and again at Cheapside, for conjuring and other matters.[iii] The latter took place in the shadow of the recently destroyed St Pauls, which had been struck by lightning and destroyed by fire and considered an ominous omen by both Catholics and Protestants.

William Cecil, Elizabeth I’s chief councillor, who served her from her accession in November 1558 until his death in August 1598, combined rumour with Coxe’s confession to convince her that “the nest of conjurors” recently broken up by The Privy council had been plotting against her. He told her that they were” conjuring and conspiring” to summons demons to kill her.[iv]Identifying a catholic conspiracy was useful to him. He was able to persuade Elizabeth to cancel the Papal Nuncios planned visit, thus discrediting Dudley, who had organised it. This combined with his wife’s recent suspicious death making him an unsuitable person to wed the queen. Cecil convinced Elizabeth that the detained priests had tried to kill her with magic.

Cecil’s treatment of the detained priests is interesting. It showed how far he was prepared to go in the struggle against Catholicism by maximising the association between Catholicism and sorcery in the public eye[v]. “The conflation of Catholicism and witchcraft was to become a fairly common trope amongst Protestants, especially Puritans in post Reformation England. “ [vi]

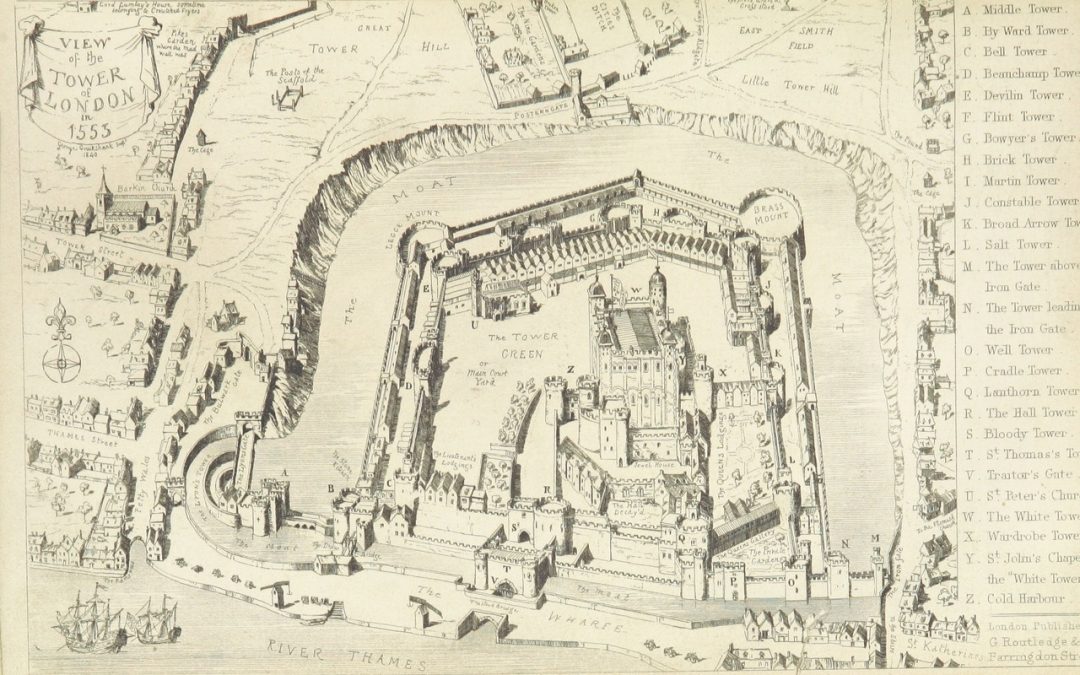

Leonard Bilson found himself a scapegoat and in the Tower of London for “papistry”. He was noted on a list of 22 prisoners in the Tower, dated 5th of September 1562, with, amongst others, Lady Katherine Grey, The Earl of Hertford and Henry Howard.[vii] To continue the Salisbury Connection, Lady Katherine Grey and her husband The Earl of Hertford are buried in Salisbury Cathedral and commemorated by The Seymour Monument.

(The Seymour monument is to Edward Seymour, Earl of Hertford, (1539-1621), nephew of Jane Seymour, third wife of Henry VIII. At his side is his wife Lady Katherine Grey (1540-1568), sister of Lady Jane Grey who was Queen of England for nine days in 1553. The kneeling figures are their sons Edward (Lord Beauchamp of Hache) and Thomas. The two were married in secret; they were both arrested and put in the tower. Whilst she was imprisoned, Catherine gave birth to 2 sons.

In 1562, the marriage was annulled and the Seymours were censured as fornicators for their “carnal copulation” by the Archbishop of Canterbury’s commission.

When Catherine died Edward was allowed out of the Tower, but officially his children remained bastards to prevent any claims of succession.)

One of John Jewel’s first tasks, as newly appointed Bishop of Salisbury was to discipline the Reverend Leonard Bilson . The disgrace to Salisbury was grievous. The Court of Arches deprived him of all ecclesiastical benefices in the Province of Canterbury on the score of “Indelible infamy.” He was cited by Bishop Jewel to appear in Chapter and show cause why he should not be deprived of his prebend. Needless to say he was unable to appear.[1]

Eight years later, in 1570, despite two applications to the Lords of the Council, Bilson was still imprisoned in the Tower. On the 14th of October 1571 he was removed, by order of the Privy Council, to Marshalsea prison where he still was in 1580 (in his early fifties.) He was eventually discharged from prison between January and March 1582 and lived for a couple of years in freedom, until his death in 1584. His will is dated 22 Oct 1584. In it he mentions a large number of books, which he wished to bequest and specific gifts of gold and jewellery.

[1] “Sarum Close “by Dora Robertson.

[i] Salisbury Cathedral by Kathleen Edwards

[ii] The Cambridge Book of Magic by Paul Foreman

[iii] The Cambridge Book of Magic by Paul Foreman

[iv] Supernatural and Secular Power in Early Modern England by Marcus Harmes

[v] Supernatural and Secular Power in Early Modern England by Marcus Harmes

[vi] Crimen Exceptum: The English Witch Prosecution in Context by Gregory J Durston.

[vii] The History and Antiquities of The Tower of London by John Whitcombe Bayley.